Here is the second chapter of my novel Terra. (Here’s the first.) I’m still not sure if I want to post the whole thing; let’s see where this goes.

=================

Chapter 2

I stared at her. She was tall and slender, with short black hair. I’m not really good at telling how old people are, but I guessed she might be about thirty. She was wearing jeans and a down vest over a plaid shirt—the same outfit she’d been wearing at the 7-11. She was very attractive. She spoke English with the slightest bit of some kind of strange accent—just enough to tell you that she wasn’t from America.

Stranger danger, my mother would say.

But I felt safe—safe enough, anyway. The woman’s eyes told me what I needed to know. “Who are you?” I asked, although I thought I knew the answer.

“My name is Valleia,” she replied.

“And . . . you’re not from here.”

She nodded. “I am not.”

“Why do you need my help?”

“Do you remember sitting in a dark church last Christmas Eve? It was not far from here, but at the same time . . . it was not here. And a stranger appeared. He explained some things to you, and he told you how to get home, when you thought you would never be able to.”

I remembered. The preacher. The traveler. When I first saw him, he was giving sermons to people who weren’t very interested. And then there was that Christmas Eve. Listen to your heart, he had told me when I was trying to figure out whether I should leave that other world, or stay with a family I had come to love.

“Is he in trouble?” I asked.

Valleia nodded. “He is. Do you have time to listen to the story?”

“Sure,” I replied.

She got down on the ground and sat crossed-legged on the soggy leaves. I sat opposite her. She closed her eyes for a moment, and then opened them. “His name is Affronius,” she began. “Affron, for short. Did he tell you anything about the world he came from?”

“Just a little. He was a kind of priest, he said. He and the other priests used the portal to go around to other worlds, other universes—’imparting wisdom,’ he said. But they tried not to interfere, even though they knew how to cure diseases and everything.”

“Well, yes, that’s true, although Affron is much more interested in imparting wisdom than most of the rest of us.”

“He was kind of…odd,” I said. “I liked him.”

“Many of us like him,” Valleia replied softly.

“What’s going on? Why is he in trouble?”

“Because of his oddness, I suppose. Larry, let me tell you about Terra.”

Terra. I must have come across that word somewhere in my reading, because it didn’t seem totally unfamiliar. But the word sounded so different, hearing it spoken by Valleia that afternoon, sitting on the damp ground in the woods behind my house.

“Terra is the name of our world,” Valleia went on. “A big part of our world is ruled by a priesthood. Affron is part of that priesthood; so am I. Some of us travel to other worlds; many others stay behind and govern our empire on Terra. This has been going on for centuries—ever since Via was discovered, really.

“What’s Via?” Like Terra, the word seemed familiar.

“Ah. I’m sorry. That’s our name for what you call the portal Anyway, there is a rule—Affron says he told you about it—that we are not supposed to change the worlds we visit. We don’t tell them how to build weapons; we don’t cure their diseases; above all, we don’t talk to them about the portal.”

“Is that why he’s in trouble? Because he talked to me?”

Valleia sighed. “That’s what he’s accused of. But . . . it’s complicated. This shouldn’t really get him into trouble. Others have done far worse things, without punishment. But Affron has powerful enemies, and they see this as a way of defeating him.”

“Is he on trial or something?”

“Yes, Larry. And Affron would like you to speak for him at the trial.”

“You mean . . . go to Terra . . . in the portal?

Valleia nodded. “To Terra. Just long enough to tell your story. Affron has told it to me—you were trapped in another world, cut off from your family, with no hope of return. It’s a powerful story. Perhaps it will move the judges. They are not easily moved, but we have to try.”

“What will happen to Affron if he’s found guilty?” I asked.

Tears suddenly began to swim in her glittering eyes. “We cannot let that happen,” she said. “We cannot let Affron die.”

“They’re going to put him to death? That’s ridiculous!”

“I know.” she said. “And we must do whatever we can to stop it. Affron’s life—and the future of Terra—is at stake.”

“The future of Terra?”

“Ah, Larry, it is too complicated to explain, and we don’t have much time. His trial is today. We must leave now, if you are going to help. I wanted to talk to you yesterday—to give you a chance to think about it—but I didn’t have a chance. So I came back.”

I could feel my pulse racing. This was the chance I’d been dreaming of—to get back in the portal and visit a different universe. The preacher’s universe.

But I remembered when Kevin and I had stepped into the portal last time. What could possibly go wrong, Kevin had said. And then, of course, everything had gone wrong.

How did I know I could trust this woman? Obviously she knew the preacher—Affron—but so what? Should I risk my life on her say-so?

Valleia’s eyes were studying me, and I suddenly understood that she was scared. Scared that I’d turn her down.

“Would I be able to come back at the exact moment I left?” I asked her.

She looked puzzled. “What?”

“You know, like no time at all passes here in my universe, even though lots of time passes in the universe I go to. That’s what happened before.”

“No,” she said. “No. That’s not what happens.”

Now I was puzzled. “Sure it is,” I replied. “I was gone for like three months before—I was in the other world from September to December—Christmas Day, actually, if you know what that is. But when I came back, it was the exact same time I left. Like I’d never been gone.”

Valleia shook her head. “I don’t understand—it doesn’t work that way. We’ll get you back here as soon as possible. But time flows at the same rate in every universe. If you stay three hours on Terra, you’ll return three hours later here on Earth.”

I didn’t understand either. I knew what had happened to me. “Maybe Affron did something?” I suggested.

She shook her head again. “It’s not possible,” she stated. And then she looked scared again, like she was losing the argument with me. “You won’t have to stay long, Larry. I promise.”

This was weird. I had just told her it was possible. Didn’t she believe me?

Knowing that I wouldn’t get back at the same time I left made it even harder to imagine going with her to Terra. She could promise all she wanted, but it didn’t sound like she was in control of things. If I didn’t get home till late at night or next morning, my mom would be a wreck. She’d call the police. She’d issue an Amber Alert or whatever it was. Volunteers would be searching the conservation land. I couldn’t do that to her, even to save Affron.

And when I finally did come back, what would I tell her and everyone else? I’d have to make up some kind of excuse. But what would it be?

It just didn’t make any sense. I shook my head. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I can’t help you.”

“A few hours of your life, Larry,” she said. “To save someone who saved you.” She sounded desperate.

I shook my head. “I just can’t,” I repeated.

We sat there on the leaves staring at each other. And then Valleia started to cry. Not in the histrionic way that Cassie cried, like whatever happened to her was the worst thing ever and we all had to pay attention—no, these were silent tears leaking out of her eyes. Like she couldn’t help herself.

She didn’t wipe them away.

I thought: maybe she’s in love with Affron. But that wasn’t my problem, was it?

I thought about my family. Matthew would be playing his video game, just like yesterday. Cassie was at rehearsal; Mom was in her home office; Dad was at work. Pretty soon Mom would start making supper and Dad would come home, and we would talk about the day in the same old way. Just like yesterday. Just like tomorrow. I hadn’t realized how much I loved my family until I almost lost them, back in the fall when Kevin and I were stuck in that other universe.

The universe that Affron had rescued us from. Shouldn’t I rescue him?

That wasn’t what made me decide. And it wasn’t Valleia’s tears. And it wasn’t curiosity, exactly. What was Terra like? I’d love to find out, but . . .

It was the sudden sense that right here, right now, I was deciding my entire future. I could go home and live my life in the usual way, and maybe it would be a great life. Maybe I’d be rich and famous and happy and never cause my mother to worry.

. . . and I would regret forever that I didn’t take this one final risk.

I had this dizzying sense of choices being made everywhere, by everyone—universes splitting and splitting again as people decided which kind of Doritos to buy, whether to bike to the harbor with Vinny or go home and write your composition, what show to watch, what college to go to, who to marry, where to live.

So many choices. So many chances for regret. I had to close my eyes to keep from falling over under the weight of the choices.

When I opened them, Valleia was still staring at me, puzzled. She had wiped her tears away. What had happened? I sensed that maybe a lot of time had passed.

“Are you all right?” she asked.

I felt okay, I thought. Maybe a little weird. “Did you just . . . do something to me?” I said.

She shook her head. “I did nothing, Larry. You seemed to go into a trance.”

I’m not sure why, but I believed her. This had all been inside me somehow.

It is only by living in doubt that we can reach certainty, the preacher—Affron—had told me.

It is only by setting out that we can finally return home.

I still didn’t know exactly what he had been talking about in his sermons. But I know that he had been talking to me when he said: Listen to your heart.

I stood up. I still felt a little dizzy, but I wasn’t going to lose my balance. I was going to be all right.

I brushed some twigs off my pants, and then I said, “Let’s go.”

“Let’s go?” Valleia repeated.

“To the portal,” I said. “To Terra.”

“Are you sure?”

I nodded.

She got up from the ground, smiled, and hugged me. “Thank you,” she whispered.

Then she led me silently through the woods. Finally she stopped in a clearing.

“Is it here?” I asked Valleia.

She nodded. “It’s here.”

She walked slowly forward. She let go of my hand, and then she stretched both of her hands out in front of her.

Something glowed a light blue beneath them.

This wasn’t what had happened to me when I entered the portal. It had been completely invisible from the outside.

The blue light faded after a second and a long dark shape appeared, extending down to the ground.

“Are you ready?” Valleia asked.

Was I ready? No, of course not. I would never be ready. But I nodded.

She went first, and I followed, leaving the woods, and my universe, behind.

When I had used the portal by myself, or with Kevin, its interior had been all foggy, like a bathroom after you’ve taken too long a shower. But this time I thought I could make out curved walls, a little out of focus. The air inside the portal was a little warmer than the air in the woods.

Valleia made some motions with her fingers, as if she was typing or playing the piano, using invisible keys. The opening we had walked through disappeared. On the opposite side of the portal, another opening appeared.

She touched my arm. “Thank you, Larry,” she said again.

And then she reached out her hand to me. I took it. She led me out the opening in the far wall of the portal, and into her universe.

but Trumbo struck me as being a very bland movie. Trumbo is presented as a secular saint, with his opponents–Hedda Hopper, John Wayne–presented as purely evil. The only flaw we see in Trumbo is when he gets cranky with his kids for not wanting to deliver some of his rewrites to a movie set–but he quickly repents and goes off to apologize to his daughter, who, like him, is devoted to the cause of justice for the downtrodden. Couldn’t we at least have had a scene where he explains why he’s still a communist despite what was then known about Stalin? Life and politics in the 1950s were more complex than this movie lets on.

but Trumbo struck me as being a very bland movie. Trumbo is presented as a secular saint, with his opponents–Hedda Hopper, John Wayne–presented as purely evil. The only flaw we see in Trumbo is when he gets cranky with his kids for not wanting to deliver some of his rewrites to a movie set–but he quickly repents and goes off to apologize to his daughter, who, like him, is devoted to the cause of justice for the downtrodden. Couldn’t we at least have had a scene where he explains why he’s still a communist despite what was then known about Stalin? Life and politics in the 1950s were more complex than this movie lets on. novel

novel

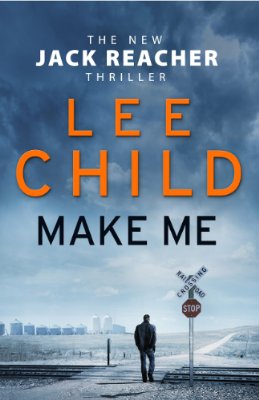

when finally revealed, makes little sense. A super-villain with no name, no past, no particular motive for his bottomless evil. Complicated set pieces in which Reacher kills or maims multiple foes due to his understanding of firearms, fighting, human psychology, etc.

when finally revealed, makes little sense. A super-villain with no name, no past, no particular motive for his bottomless evil. Complicated set pieces in which Reacher kills or maims multiple foes due to his understanding of firearms, fighting, human psychology, etc.