Everyone seems to love The Girl on the Train. It was a number one best seller; it’s being made into a movie; it’s on Obama’s summer vacation reading list. So fine. I just read it on my summer vacation.

The first thing I noticed is that the author used the technique I have settled on for my new novel: the point-of-view character is identified at the beginning of each chapter (along with the date and time of day). I have become a little dubious about this technique since my

writing group reviewed my latest chapters, and Jeff pointed out that I hadn’t correctly established my point-of-view character in one of them. “But I don’t need to,” I said. “The point-of-view character is identified in the chapter title.”

“Oh,” Jeff replied. “I hadn’t noticed that.”

So maybe I need to remove the “Chapter” designation; maybe I need to make the name of the character bigger. That’s what Paula Hawkins does. It’s probably all that stands between me and a deal for a major motion picture.

Anyway, her novel is well written and cleverly constructed, but I ended up being pretty disappointed. Here are the problems I had with it (moderate spoiler alert):

- I figured out who the murderer was pretty early on. I kept expecting there would be a further twist, but the twist never came.

- The critical event in the plot is witnessed by one of the narrators, but she doesn’t remember what happened because she was having an alcoholic blackout. Or perhaps it didn’t happen. Or perhaps she remembered it incorrectly. But finally she remembers it, and that solves the mystery. Meh.

- One of the other narrators solves the mystery because the murderer unaccountably holds onto a key piece of evidence against him. Phooey.

- The climax is straight out of a Lifetime movie. Woman finally realizes that the man she loved is really a lying cheating murdering psychopath. The man comes after her. Can she summon up the moxie to defeat him? Ugh.

But really, her chapter titles are pretty good.

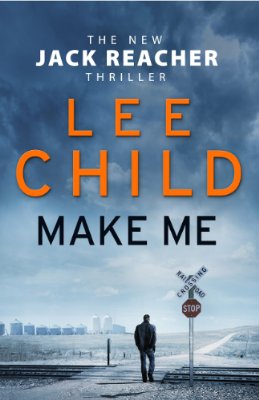

when finally revealed, makes little sense. A super-villain with no name, no past, no particular motive for his bottomless evil. Complicated set pieces in which Reacher kills or maims multiple foes due to his understanding of firearms, fighting, human psychology, etc.

when finally revealed, makes little sense. A super-villain with no name, no past, no particular motive for his bottomless evil. Complicated set pieces in which Reacher kills or maims multiple foes due to his understanding of firearms, fighting, human psychology, etc.