My publisher in its wisdom has reduced the ebook price of my novel Senator to $0.99. Probably trying to get rid of unsold inventory or something. Buy it before they run out! On Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

Tag Archives: novels

I’ve finished the first draft of my novel!

So, from my perspective, it’s turned from an idea to a thing. A thing that needs a lot of rewriting and reworking, but it’s real. It exists. I think I’ll take tomorrow off and run in a road race.

A nice review for “The Portal”

On Amazon:

The book is primarily written for the pre-teen or early teenager, I believe anyway, but I really enjoyed it. The characters pre teens in their world, were transferred to another world, in a different time, to a war torn New England where New Portugal and New Canada were going to attack New England. The boy’s, in conversation with army officers, gave ideas to the Army of New England for weapons that could change the outcome of the war. I haven’t enjoyed a simple, nonsexual, non-cussing book in a long time such as this book is. I recommend this to any boy, I’m not sure about girls since there aren’t many girl characters in it. There is a message in it about family, even families who might have issues and personality problems; about loneliness and familial love; about goodness and evil; about prayer in time of despair. It is not a God book, but it has a spiritual bent, especially when the war starts. For the most part, the main characters are all honorable, even those characters who might seem to be dishonorable, especially those who have come in contact with our two hero’s, in both worlds.

I can’t recommend this book enough.

That sounds about right!

I just hope the reader doesn’t try out some of my other novels, which fall pretty clearly in the “cussing” category, as several annoyed commenters have pointed out.

World-building and storytelling

Posting has been light while I’ve tried to meet my goal of finishing the first draft of my novel in six months. I probably won’t make it, but I’ll come close.

This is a sequel to my novel The Portal, and the experience of writing it is interestingly different from my previous effort: writing another novel in The Last P.I series, which turned out to be Where All the Ladders Start. Both novels are science fiction, but Where All the Ladders Start uses a future world (and a set of characters) that I’ve already created. The challenge in writing it was coming up with another mystery plot (or two) for my protagonist to get involved in.

The sequel to The Portal takes place in a parallel (or alternative, or maybe alternate) universe. It’s an adventure story rather than a mystery, so the plot doesn’t have to be as tightly wound as that of Where All the Ladders Start. But I have to do a whole lot of world-building for it, and that offers its own difficulties. There are two things that have been happening in the course of the first draft:

First, I keep coming up with new ideas about the world. Some are just local color to give the novel added depth; others are dictated by the plot (which, as usual, has veered off in unexpected directions as I write). All that stuff needs to be worked into the second draft. This is pretty much business as usual.

Second, and more interesting, there’s material I wanted to work into the novel, but I never seemed to find the right place for it. Now what? Will I have better luck in the second draft? The problem I’m having is the world-building does not always play well with storytelling. For example, at one point in the draft I thought I had reached a good spot in the book where a character could spend a few pages giving some needed background, but my writing group gave the scene a unanimous thumbs-down: it slowed the action too much, I was informed. Ditch the exposition and ramp up the conflict. The best science fiction novels make integrating the description of the fictional world with the action of the plot seem natural; but it’s hard work. At least for me. The challenge of the second draft is going to be making that hard work look effortless.

Should Charlie Hebdo get an award?

PEN wants to give Charlie Hebdo its “freedom of expression courage” award. This has provoked an outcry from many writers. PEN isn’t backing down, saying that they reject the “assassin’s veto”.

My son lives in the Middle East, and he was baffled by the “Je Suis Charlie” thing. Why isn’t the West protesting the many courageous Muslim bloggers and journalists being persecuted by autocratic governments in the Middle East and elsewhere? Well, fair enough, I’m happy if they get awards too. But I’m a part of the West, and free speech is one of the things the West does right. As a writer, that matters to me.

Nowadays, the “most helpful” review of my novel Senator on Barnes & Noble is a one-star review complaining that it used the Lord’s name in vain multiple times at the beginning, so the anonymous reviewer read no further. Again, fair enough. Readers who don’t approve of using the Lord’s name in vain have been warned. But nowadays I could easily imagine a world where offending religious people like my anonymous reviewer would be illegal (especially in Europe); or, where corporations like Barnes & Noble would decline to sell books that contained certain words or phrases deemed offensive to a religion. (Does Barnes & Noble sell books that contain imagines of Mohammed? I have no idea.)

I have this sense that conventional liberalism has lots its way over this issue–or at least, it’s too vexing an issue for liberals to respond to it coherently. What happens when two core liberal values–diversity and freedom of speech–collide? When blacks on campus claim they are the victims of hate speech? When Muslims claim they have been scapegoated for the actions of a few crazy terrorists? Do we have to parse all of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons to determine if the magazine is worthy of an award?

Here’s a paragraph from the PEN statement that I like very much:

The rising prevalence of various efforts to delimit speech and narrow the bounds of any permitted speech concern us; we defend free speech above its contents. We do not believe that any of us must endorse the content of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons in order to affirm the importance of the medium of satire, or to applaud the staff’s bravery in holding fast to those values in the face of life and death threats. There is courage in refusing the very idea of forbidden statements, an urgent brilliance in saying what you have been told not to say in order to make it sayable.

Good for them.

No! Not an unreliable narrator!

In my post about first person narrative, I forgot to mention the sub-genre of unreliable first-person narrators. In my misspent book-reading youth I was quite enamored of such contrivances, even though I’ve never bothered with them in my own writing. An obvious example of an unreliable narrator is Huckleberry Finn, who often doesn’t quite understand the events or people he’s describing, so readers have to intuit what’s really happening.

But that’s pretty straightforward. More interesting, to me at any rate, are narrators who at first seem to be reliable, but whom we gradually realize aren’t, thereby requiring us to reassess the entire story. Just typing that sentence makes me want to re-read Nabokov’s Pnin and Pale Fire, which blew me away when I first read them decades ago.

I watch movies more than I read books nowadays (they’re shorter!), and unreliable narration seems to show up constantly in films and even in TV shows. Mad Men does it all the time. In last week’s episode (the first episode of the last half-season), we suddenly see one of Don’s old flames modeling a chinchilla coat for him. We are never told that this didn’t actually happen–we just have to figure out what’s going on in reality and what’s going on in Don’s somewhat enigmatic imagination.

The one time I really didn’t expect unreliable narration was in Hitchcock’s movie Stage Fright. This is a straightforward Hitchcock thriller, except for an early flashback that (spoiler alert) turns out to be a false version of a murder.

No! Not an unreliable narrator!

IMDB tells us that audiences were baffled and then enraged by this device, and I think I read somewhere that Hitchcock later called it the worst directorial decision he made in his career. It certainly gives you a jolt.

As I said, I don’t do this sort of thing in my writing, but I find myself close to the Huckleberry Finn style of unreliable narration sometimes in The Portal and its sequel, both of which are narrated by a young teenager. Sometimes, to be true to his character, he can’t be allowed to quite understand what’s going on.

I hope this doesn’t enrage my readers.

So that’s what my novel is all about!

When I’m writing a novel, there usually comes a point when I realize what it’s all about. Not the details of the plot–working them out is a constant process–but the reason I’m bothering to write it. It’s a bit odd that I never seem to figure this out before I starting in on the thing, but there you have it.

Anyway, I’m deeply into the first draft of the sequel to my novel The Portal, and I find that I have suddenly reached this point. Which is a considerable relief, actually. Now I’m not just telling a story; I’m telling a story that matters to me.

God’s Bankers and Pontiff: Too Improbable for Fiction

A major subplot of my twisty thriller Pontiff involves the secretive Vatican Bank and a new pope’s desire to clean it up. There’s a new book out called God’s Bankers by Gerald Posner that goes into 700 pages worth of detail on just this subject. It’s been getting rave reviews all over the place, including the New York Times. Much of what Posner talks  about is familiar to me from my reading when I was working on Pontiff — for example, this:

about is familiar to me from my reading when I was working on Pontiff — for example, this:

Posner’s gifts as a reporter and storyteller are most vividly displayed in a series of lurid chapters on the American archbishop Paul Marcinkus, the arch-Machiavellian who ran the Vatican Bank from 1971 to 1989. Notorious for declaring that “you can’t run the church on Hail Marys,” Marcinkus ended up implicated in several sensational scandals. The biggest by far was the collapse of Italy’s largest private bank, Banco Ambrosiano, in 1982 — an event preceded by mob hits on a string of investigators looking into corruption in the Italian

banking industry and followed by the spectacular (and still unsolved) murder of Ambrosiano’s chairman Roberto Calvi, who was found hanging from scaffolding beneath Blackfriars Bridge in London shortly after news of the bank’s implosion began to break. (Although the Vatican Bank was eventually absolved of legal culpability in Ambrosiano’s collapse, it did concede “moral involvement” and agreed to pay its creditors the enormous sum of $244 million.)

But I didn’t know this part, which seems too improbable to put into a thriller:

In one of his biggest scoops, Posner reveals that while Marcinkus was running his shell game at the Vatican Bank, he also served as a spy for the State Department, providing the American government with “personal details” about John Paul II, and even encouraging the pope “at the behest of embassy officials . . . to publicly endorse American positions on a broad range of political issues, including: the war on drugs; the guerrilla fighting in El Salvador; bigger defense budgets; the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan; and even Reagan’s ambitious missile defense shield.”

I don’t suppose I’ll have the time or the energy to read the book. The story makes wonderful fodder for thrillers, but it’s pretty depressing to realize that this is real life.

First person, third person

I continue to intermittently make my way through Lee Child’s oeuvre, and I recently listened to The Enemy, from 2004.. It has much of what I’ve come to expect from a Jack Reacher novel: a crackerjack (if occasionally absurd) plot, much gratuitous violence, well-developed (if occasionally absurdly villainous) characters, and a ton of background information, some interesting, some not so much (for example, there is a multi-page essay on crowbars that I could have done without).

What’s different about The Enemy is that it’s told in the first person (and, less importantly, it’s a prequel, taking place back in 1990, when he was still in the military). I didn’t know you could mix third-person and first-person narrative in a series! Does anyone else do it? It works just fine, although I always have the same reaction to first-person stories like The Enemy: when is the narrator writing this story down? Why?

This sort of baffles me in the books in my first-person Last P.I. series (the most recent of which, Where All the Ladders Start, is available at fine online retailers everywhere!). Walter’s friend Art, proprietor of Art’s Filthy Bookstore, is always badgering him to write up his cases, and Walter is always making excuses about why he can’t do it. But in fact, here we are reading the first-person narratives.of those very cases. How did that happen? Is Walter lying to Art? Does the writing take place some time in the future? No explanation is given, perhaps because no explanation is possible.

I’m pretty sure I’m the only one who worries about stuff like this.

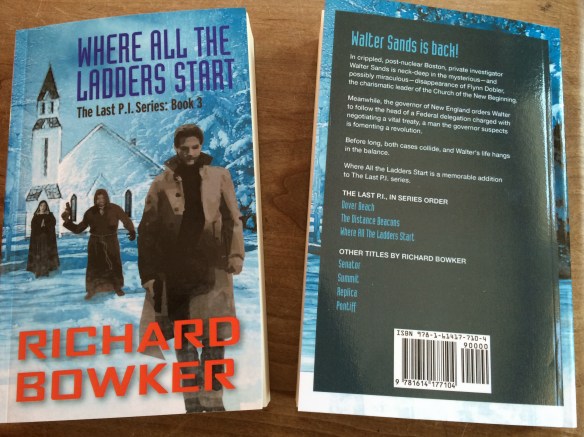

“Where All the Ladders Start”: The printed books have arrived!

Here’s what the book looks like:

I’m all in favor of ebooks, but physical books do seem more “real,” don’t they?

But here’s the problem you run into with printed books: My publisher got complaints about the point size of the font they use, so they upped it from 10-point to 12-point. This means that, instead of being about 300 pages, the book ends up being a lengthy 392 pages. Which means that they have to charge more for it than, for example, The Portal: $17.95 retail.

I can get you a discount, though.